Florencia Sanguinetti: The Grand Debut

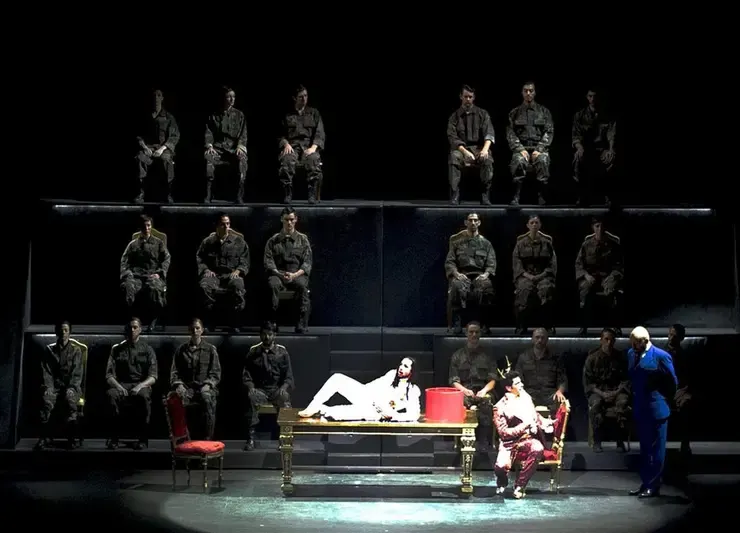

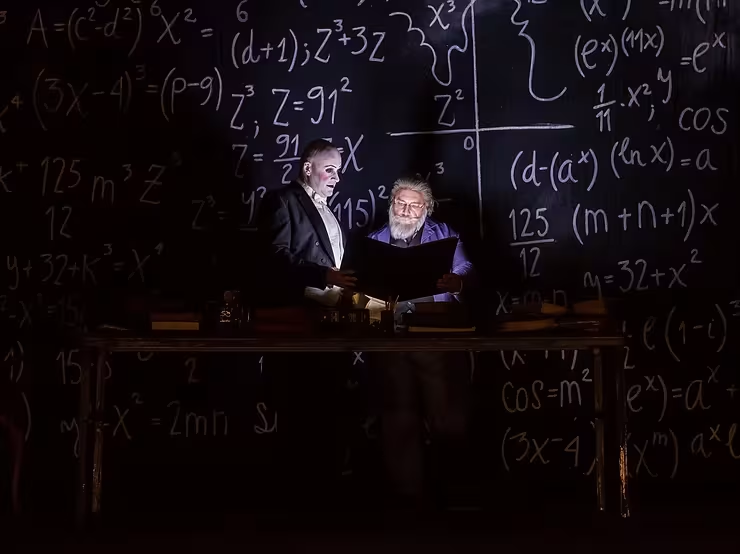

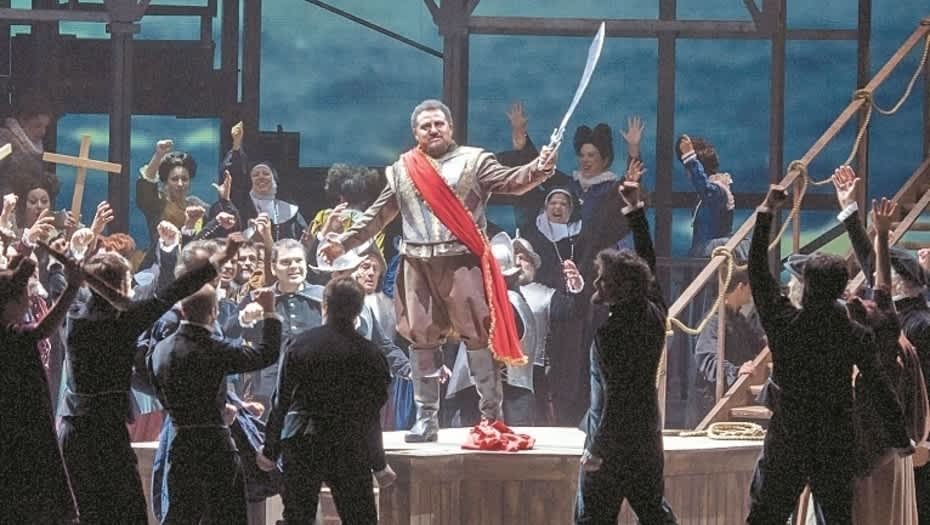

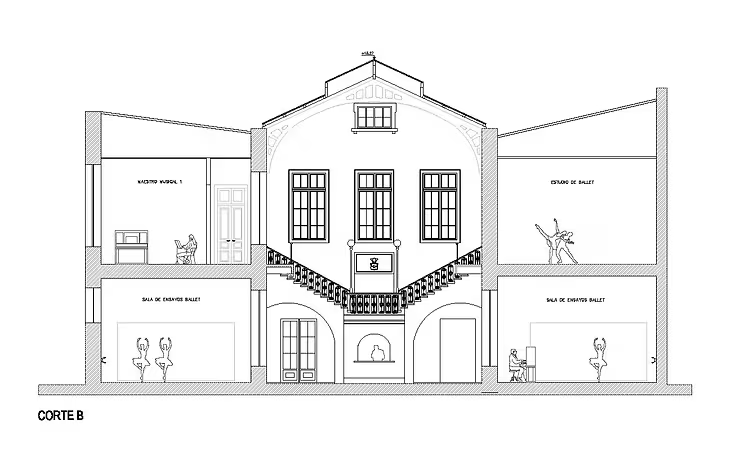

With the stage direction of Prokofiev's 'The Fiery Angel,' the ISAT graduate will become one of the first women to take on that role at the Colón. In her environment. Sanguinetti is a graduate of the Instituto Superior de Arte del Teatro Colón. She arrived at the stage direction. Photo: Gustavo Castaing. 14 years after the last staging of 'The Fiery Angel' at the Colón, Sergei Prokofiev's opera, with a libretto by the composer himself, returns to the theater today; this time with stage direction by Florencia Sanguinetti. The staging will also mark her debut in directing at the premier Argentine coliseum, which will make her one of the few women who, in her own words, has come 'to fulfill the dream to which any stage director dedicated to opera aspires.' Of her 45 years, Sanguinetti has spent 25 working in the theater, from whose Instituto Superior de Arte del Teatro Colón (ISAT), where she graduated as a regisseur. The work of assistant director put her in the challenge of collaborating with very demanding directors. However, she barely remembers three female directors: Olivia Fuchs, who staged 'Pelléas and Mélisande,' Catherina Wagner, remembered for having abandoned her own project of an abbreviated Tetralogy, and the Argentine Valentina Carrasco, resident in Barcelona and best known for her collaboration with La Fura dels Baus, who arrived to resolve what Wagner had left unfinished. But her case is different. 'I grew up in this theater, it's my natural environment. So I recognize that I always expected this moment to come,' she says. How did the environment treat you? Although it's a very competitive environment, I felt a lot of solidarity and generosity from all sectors of the theater. It's a very masculine environment, but fortunately there's no machismo. 'The Fiery Angel' doesn't seem to be an easy title to resolve. It's true. The main difficulty lies in the constant discontinuity of events. But you also have to solve the long scene of the first act, that kind of recitative in which Renata, the protagonist, narrates that the angel of light, who is the demon, appears to her. Everything is narrated in a monologue in which Prokofiev summarized a large part of the novel. Does Prokofiev give any guidance to resolve these dramatic and scenic difficulties? The score doesn't have stage markings, but reading the original book, one realizes that the synthesis he made is very consistent with the essence of the work. What he didn't put wasn't necessary. What is your solution for these difficulties you talk about? I use a generic spatial device, an organic space where the whole opera takes place. The set designer, Enrique Bordolini, and I liked to think of something anatomical that was ambiguous at the same time. How will you use the carousel that you included on stage? It's part of the many elements that will appear throughout the work. I was interested in disconcerting, generating the confusion that appears in the novel, in which temporal relationships are not understood, where scenes are interrupted and everything breaks. This will also be reflected in simultaneous events that have completely different moods. But could you give something resolved in a work of this kind? I've seen versions that try to follow a line, but it seems to me that they take away interest from the work, whose plot is not the important thing. What's interesting is the number of interpretations it triggers. Being a symbolist work, it's surprising to see so many objects on stage, characterized to the smallest detail. Will so much figuration create greater confusion? There are moments in the staging that we have decided to resolve with tremendous realism, although I have a deep rejection of it, as this opera undoubtedly also expresses. The very idea of symbolism is the rejection of realism. And the staging, although it plays with realistic elements, is not at all. However, there are situations that must be resolved explicitly. Why? Because in theatrical language, impact is very important, not only of poetry, but also of staging. The carousel is very useful to me theatrically, because it's an element of Renata's imagination, a memory from when she was little, but it also appears as something sinister. It's a resource that helps me move from one scene to another, to include a certain notion of time. It's an element that will always appear in the background. As assistant director of the production of 'The Elixir of Love,' you were very close to Sergio Renán in his last days. How were those days? I loved Sergio very much. His loss was very painful, not only for me. The entire work team misses him. We had to work with him when he was very ill; he had already had a tracheotomy, and he couldn't speak. But I'm not exaggerating if I tell you that he had a devastating work energy. He had many physical limitations, but his energy was unstoppable. How was the relationship you maintained with him during that period? In that last staging, he confidentially asked me to be his interpreter. It was moving to see him work in those conditions. He disappeared before the premiere. After one of the group rehearsals, Sergio was hospitalized and we never saw him again. It was very hard for everyone to cope with the production in that situation. It's strange; his death was surprising to us. But the panorama you describe doesn't seem to be very encouraging. It was because beyond his illness, we saw him very active; he had resurrected so many times from terrible things, that I think we completely denied what was happening. We convinced ourselves that he would get away with it again. Sergio enjoyed life very much. The day he was honored for the 40th anniversary of 'La Tregua,' we went together to see the restoration, within the framework of the BAFICI. I remember him telling me: 'You don't know, girl, what I would give to be 40 again.' He really felt that he had the energy to start his life again. And when he passed away, I had been commissioned to restage 'The Elixir...' in Montevideo. The whole team went in his name. In the rehearsals, we seemed to see him every time we repeated the things he had indicated here. He was always present. We felt, on the one hand, the joy of having had him, and on the other, the emptiness of knowing that he will no longer be there. The staging will be in its original language. 'The Fiery Angel,' the third inclusion in the field of opera by composer Sergei Prokofiev, born in Ukraine in 1891, is based on the novel by Valery Briussov, an icon of Russian symbolism. In the voice of its protagonist, Renata, the novel narrates the appearance of an angel of light, a demonic figure that first seduces her and then subdues her. In a way, with this work Prokofiev aligns himself with a type of more stark and violent production, in the manner of expressionism. However, throughout its five acts, the piece does not lose its fantastic tone. Although the composer worked on the work between 1919 and 1923 –he corrected it later, between 1926 and 1927--, he had no possibility of seeing its premiere. There were several unfulfilled representation promises. Bruno Walter himself, director of the Berlin State Opera, failed in his effort to premiere it in 1926. Only almost two years after the composer's death, in November 1954, 'The Fiery Angel' was premiered at the La Fenice theater in Venice. The Teatro Colón represented it for the first time in Italian, in 1966, with direction by Bruno Bartoletti and staging by Virginio Puecher. In 1971, it was restaged in the same language with conduction by Bartoletti and régie by Ernst Poettgen. This time, it can be heard in Russian, its original language. Four nights with Prokofiev. 'The Fiery Angel' goes on today, 6, 8, and 10 of this month, at the Teatro Colón. Direction: Ira Levin; staging: Florencia Sanguinetti. Cast: Ruprecht, Vladimir Baykov; Renata, Elena Popovskaya; Agrippa von Nettesheim; Mephistopheles, Roman Sadnik; Inquisitor, Iván Garcia/Cristian De Marco.